Water security a matter of national security

Oliver Brandes, Merrell-Ann Phare

Published in The Hill Times, October 2025

The newly-formed Canada Water Agency, overseen by Environment Minister Julie Dabrusin, pictured, must have the clear authority and resources to support programs that work, all while deepening collaboration in regions across the county, write Oliver M. Brandes and Merrell-Ann Phare. The Hill Times photograph by Andrew Meade

Water will define Canada’s next century.

The only question is: will we be ready?

The warning signs are everywhere. Devastating floods. Record-breaking droughts. Long-term boil-water advisories that hit Indigenous communities hardest. Heat domes, atmospheric rivers, and wildfires that threaten towns across the country. These aren’t isolated events. They point to a deeper crisis.

Canada must rethink how we manage and govern water.

While governments wrestle with budgets and shifting relations with the United States, one fact stands out: water security is national security. Canada needs to prioritize water and act accordingly.

The Americans already have. The U.S. Global Water Strategy recognizes that “secure and sustainable access to safe water is an essential element of national security.” The threats are mounting. In 2024, Russian-linked hackers targeted multiple Texas water systems, causing tank overflows. Even closer to home, the International Joint Commission—the body that manages waters along our nearly 9,000-kilometre border—was hit by ransomware. Water systems aren’t just environmental resources. They’re critical infrastructure and prime security targets.

Canada and the U.S. share responsibility under the 1909 Boundary Waters Treaty. With Washington, D.C., treating water as a security issue, the chance for deeper co-operation is real. But only if Canada develops its own strategic water security framework. Without this, we risk being sidelined as the junior partner in managing our most vital resource. The threat to our sovereignty would only intensify.

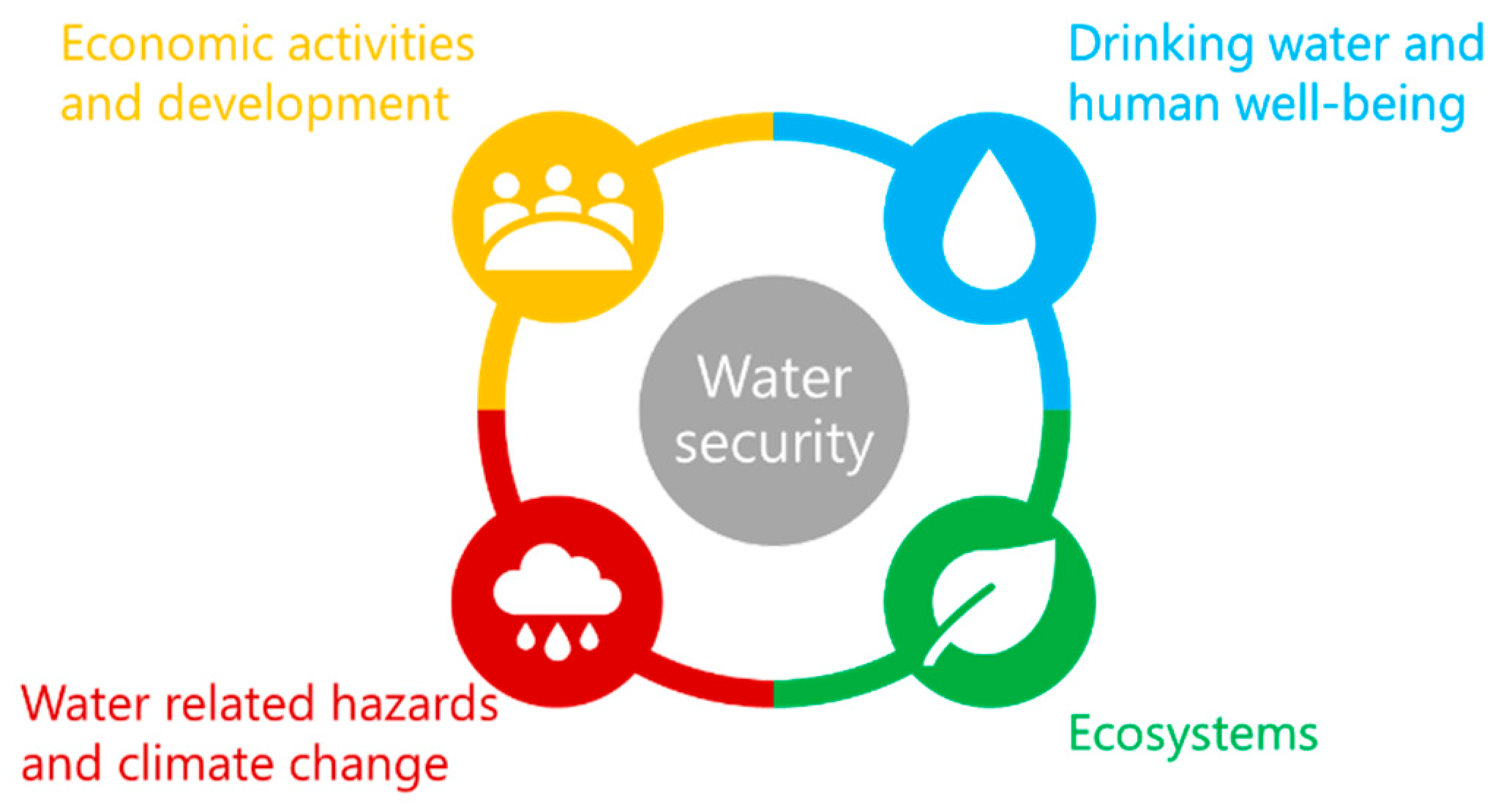

Graphic from Marcal, J.; Antizar-Ladislao, B.; Hofman, J. Addressing Water Security: An Overview. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13702. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413702

Why water security

Water security rests on three pillars. Together, they match the core of national security:

Protecting quality and quantity. Communities and ecosystems need clean, safe, dependable water flows. Without them, public trust erodes, health declines, and economies stall.

Building resilience. Aquifers, rivers, dams, watersheds, and treatment plants are the backbone of our communities, economy, and health systems. They must be treated as interconnected critical infrastructure, not isolated assets.

Strengthening governance and co-governance. Every government with authority—federal, provincial, territorial, and Indigenous—needs a proper seat at the table. That means embedding the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, and respecting Indigenous knowledge systems and water rights. Recognizing the rights of Indigenous nations and Indigenous knowledge systems in water management is fundamental to building true security.

These elements converge and intersect with every major security challenge of our time: climate change, energy and food supply, cross-border conflict, and emergency preparedness. Water doesn’t respect borders. Managing and effectively governing water requires deep co-operation and a stronger commitment to working hard at collaboration.

A Canadian way forward

Canada can embrace water security as national security while amplifying our core values. Those values—co-operation, balance between prosperity and stewardship, and genuine partnership with Indigenous nations—are our strategic advantage.

The starting point, and a major strategic advantage, is the newly formed Canada Water Agency. To have the impact needed, it must have the clear authority and resources to focus on impacts and support programs and institutions that work, all while deepening collaboration in regions across the county and actively addressing priority water challenges.

Canada also needs to strengthen its hand at the border. With the U.S. moving fast, we must be ready to engage as equals. That means upholding collaborative federalism and Indigenous co-governance—turning our co-operative instincts into strategic advantages.

The next security frontier

Security evolves. In the 2000s, we added cyber security. In the 2010s, pandemic preparedness. In the 2020s, it must be water.

Treating water as security broadens responsibility beyond a few departments in Ottawa. It demands whole-of-government leadership. Defence, Public Safety, and the Communications Security Establishment all have roles to play—alongside provinces, territories, and local and Indigenous governments.

With the explicit co-ordinating function of the Canada Water Agency and our longstanding binational partnership through the International Joint Commission, the opportunity sits before us. This means dedicated funding. Long-term planning. Political recognition at the highest levels.

Governments can’t make it rain, but they can help communities prepare for what’s ahead and ensure everyone does their part. Canada’s national security—and indeed our future—depends on reliable, clean, and well-governed water.

Oliver M. Brandes is co-director of the POLIS Project on Ecological Governance and associate director of the Centre for Global Studies at the University of Victoria. Merrell-Ann Phare is a lawyer, negotiator, and executive team lead at the Centre for Indigenous Environmental Resources. They are members of the Forum for Leadership on Water (FLOW), co-authors of the report Water Security for Canadians: Solutions for Canada’s Emerging Water Crisis, and were panellists at the recent Massey College conference “Ensuring the Flow: Water Security for Canada and the World.”